Device-Cloud-Protocol¶

Preface¶

This document will provide a general introduction in the way devices communication with the cloud in the Bifravst project. Communication is the most important aspect to optimize for when developing an ultra-low-power product because initiating and maintaining network connection is relatively expensive compared to other device operations (for example reading a sensor value). It is therefore recommended to invest a reasonable amount of time to revisit the principles explained here and customize them to your specific needs. The more the modem-uptime can be reduced and the smaller the total transferred amount if data becomes, the longer will your battery and your data contingent last.

NB-IoT as the cellular connection¶

The firmware is configured to operate in NB-IoT mode to connect to the cellular network (albeit using TLS over TCP which is most likely not available in other NB-IoT networks outside of Norway).

MQTT as transport protocol¶

Bifravst uses MQTT to connect the device to the cloud provider.

The MQTT client ID defaults to the IMEI of the device.

JSON as a data format¶

Bifravst uses JSON to represent all transferred data. If offers very good support in tooling and is human readable. Especially during development its verbosity is valuable.

Possible Optimizations¶

As a data- and power-optimization technique it is recommended to look into denser data protocols, especially since the majority of IoT applications (like in the Cat Tracker example) will always send data in the same structure, only the values change.

Consider the GPS message:

{

"v": {

"lng": 10.414394,

"lat": 63.430588,

"acc": 17.127758,

"alt": 221.639832,

"spd": 0.320966,

"hdg": 0

},

"ts": 1566042672382

}

In JSON notation this document (without newlines) has 114 bytes. If the message were to be transferred using for example Protocol Buffers the data can be encoded with only 62 bytes (a 46% improvement) (source code).

Note that even though the savings in transferred data over the lifetime of a device are significant, there is an extra cost of maintaining the source code on the device side and on the cloud side that enables the use of a protocol that is not supported natively by the cloud provider.

See also: RION Performance Benchmarks

FlatBuffers seems like the best candidate for a resource constraint device like the 9160.

The four kinds of data¶

Note

This segment is also available as a stand-alone blog post on {DevZone.

Data Protocols¶

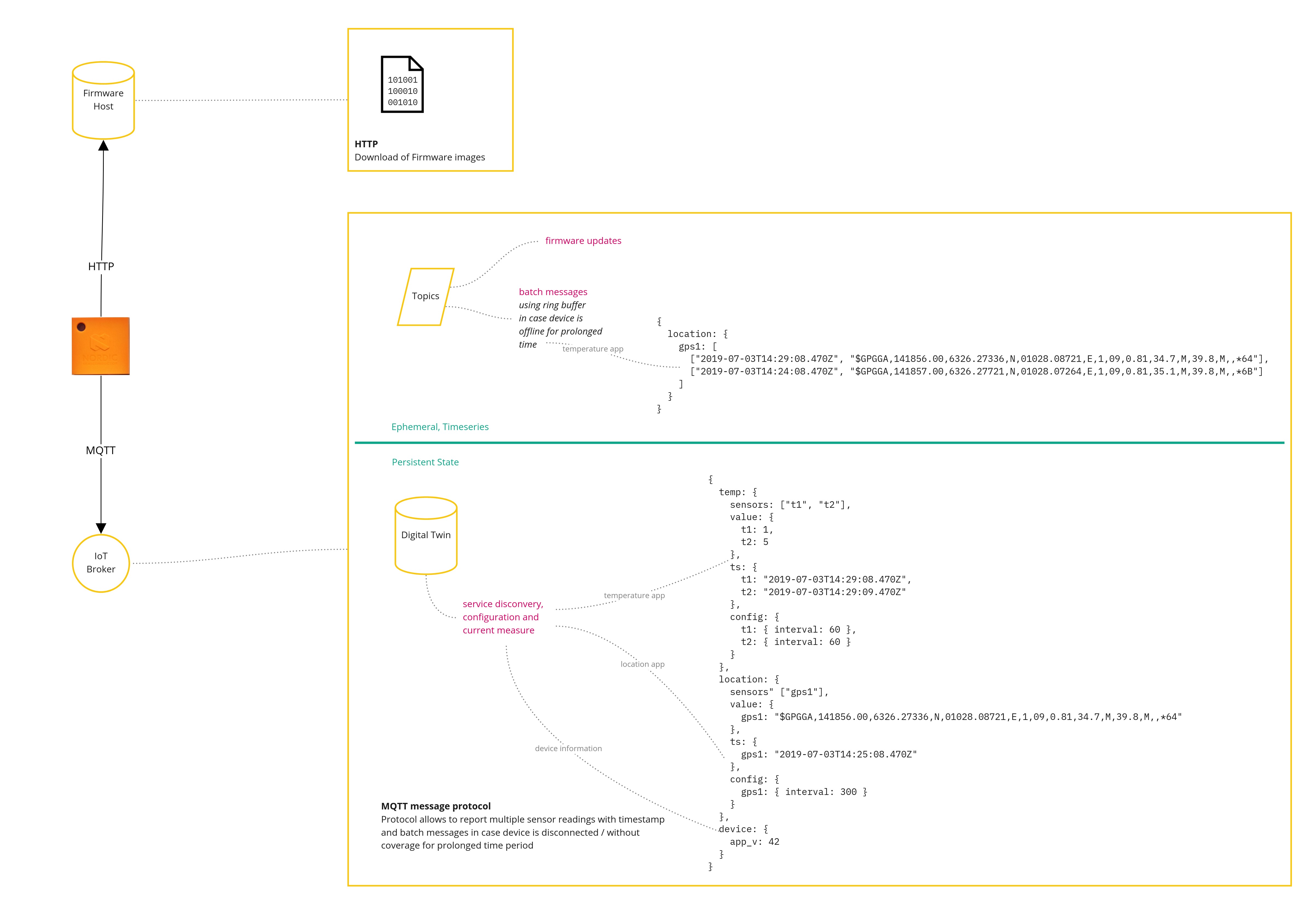

1. Device State¶

The Cat Tracker example needs to communicate with the cloud in order to send position updates and information about it’s health, first an foremost is the battery level a critical health indicator. This data is considered the device state. Because we want to always be able to quickly see the latest state of the device, a digital twin is used to store this state on the cloud side: whenever the device sends an update, the digital twin is updated. This allows the web application to access the most recent device state immediately without needing to wait for the device to connect and publish its state.

It is an important criterion for the robustness of any IoT product to gracefully handle situations in which the device is not connected to the internet. It might even not be favorable to be connected all the time—wireless communication is relatively expensive consumes a lot of energy and therefore increases the power consumption.

Note

The Cat Tracker example is optimized for ultra low power consumption, we want to turn off the modem as quickly as possible and keep it off as long as possible.

This is achieved by making the device smart and allowing it to decide based on the situation whether it should try to send data.

In passive mode, data is sent when movement is detected: the accelerometer wakes up the application thread which then tries to acquire a GPS fix and a cellular connection. If there is no longer movement detected, the modem will be turned off and the application goes back to sleep. The passive mode is designed to conserve as much energy as possible, nevertheless we want the device to once in a while send an update, so we know about its battery condition and in case the motion sensor stops working properly.

2. Device Configuration¶

Optimizing this behavior takes time and while the devices are in the field sending firmware upgrades for every change (more about that later) will be expensive. We observe firmware sizes of around 500 KB which will, even when compressed, be expensive because it will take a device some time to download and apply the upgrade, not to mention the costs for transferring the firmware upgrade over the cellular network. Especially in NB-IoT-only deployments is the data rate low. Upgrading a fleet of devices with a new firmware involves orchestrating the roll-out and observing for faults. All these challenges lead to the ability to configure the device, which allows to tweak the behavior of the device until the inflection point is reached: battery life vs. data granularity. Interesting configuration options are for example the sensitivity of the motion sensor: depending on the tracked subject what is considered “movement” can vary greatly. Various timeout settings have an important influence on power- and data-consumption: the time the device waits to acquire a GPS fix, or the time it waits between sending updates when in motion. Finally the device can be put in an active mode, where it sends updates based on an configurable interval (of course) regardless whether motion is detected or not. This is great when actively developing the firmware with individual devices or when debugging the device behavior in specific areas and situations.

On the other hand is device configuration needed if the device controls something: imaging a smart lock which needs to manipulate the state of a physical lock. The backend needs a way to tell the device which state that lock should be in, and this setting needs to be persisted on the cloud side, since the device could lose power, crash or otherwise lose the information if the lock should be open or closed.

Here again is the digital twin used on the cloud side to store the latest desired configuration of the device immediately, so the application does not have to wait for the device to be connected to record the configuration change. The implementation of the digital twin then will take care of sending only the latest required changes to the device (all changes since the device did last request its configuration are combined into one change) thus also minimizing the amount of data which needs to be transferred to the device.

Timestamping¶

Device state and configuration are timeless datum, they apply always and absolutely.

The device sends a GPS position over the cellular connection and the digital twin is updated, we now know where the device is now.

When the device configuration is changed (A -> A') the device will eventually apply the new configuration, and if another configuration change was made while the device was not connected (A' -> A'') the device can directly jump to A''.

To make state and configuration changes available over time we can store all changes on the cloud side with the time of the change and make them available for retrieval in a time-series fashion.

Time is relative.

This approach has an inherent problem: if we are to store the battery level measured by the device with the time it was received by the cloud, the timestamp will not be accurate. It can take minutes between the sampling of the battery voltage and the time the update is finally delivered on the receiving end, because for example it took the device a while to establish the cellular connection in order to send the update. While this might be acceptable with a sensor that has low volatility, it might not be acceptable in scenarios where it is important to exactly know when something happened. Imaging you are tracking parcels and want to track if a parcel is dropped. A few minutes can make a big difference to pinpoint the exact situation when the parcel is being moved by a person or even in a vehicle.

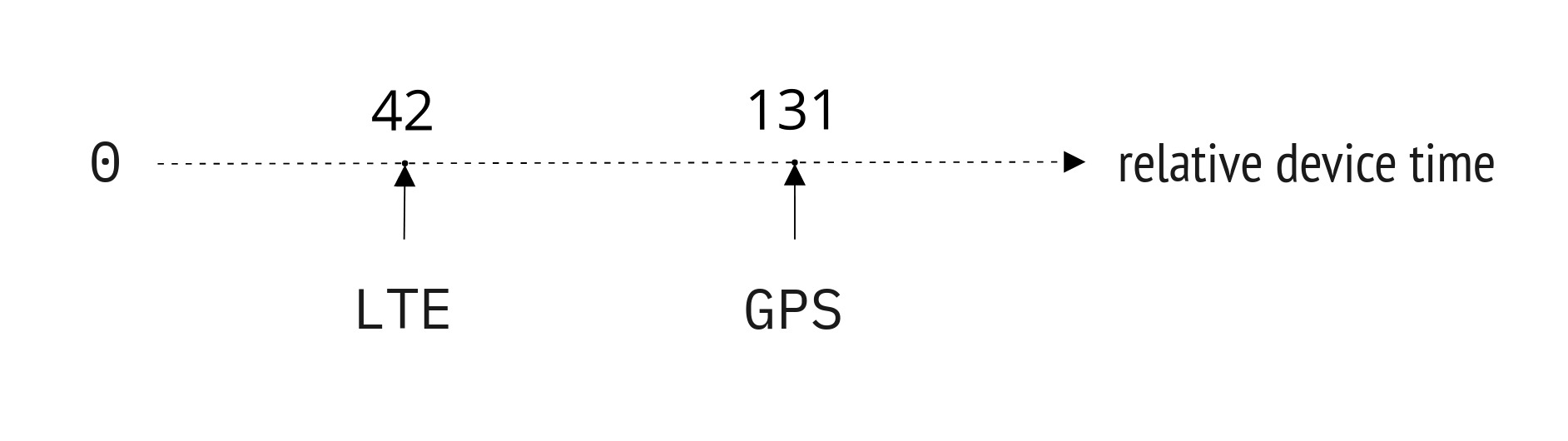

The need for precise time measurement on the device is important and is achieved by combining three time sources: the relative device timestamp (a relative time with microsecond resolution that counts upwards from zero after the device is powered on), the cellular network time and the time from the GPS sensor.

Timestamping¶

Every time a sensor is read, the value is recorded with the device timestamp. Once theses measurements are about to be sent (in which case there is a cellular connection and at least the network time is known), the relative timestamps can be converted to absolute timestamps using the relative timestamps of the network or the GPS time.

This way all data is sent with precise timestamps to the cloud where the device time is used when visualizing data to accurately reflect when the datum was created.

3. Past State¶

Imagine a reindeer tracker which tracks the position of a herd. If position updates are only collected when a cellular connection can be established there will be an interesting observation: the reindeers are only walking along ridges, but never in valleys. The reason is not because they don’t like the valley, but because the cellular signal does not reach deep down into remote valleys. The GPS signal however will be received there from the tracker because satellites are high on the horizon and can send their signal down into the valley.

There are many scenarios where cellular connection might not be available or unreliable but reading sensors work. Robust ultra-mobile IoT products therefore must make this a normal mode of operation: the absence of a cellular connection must be treated as a temporary condition which will eventually resolve and until then business as usual ensues. This means devices should keep measuring and storing these measures in a ring-buffer or employ other strategies to decide which data to discard once the memory limit is reached.

Once the device is successfully able to establish a connection it will then (after publishing its most recent measurements) publish past data in batch. Here again we need to make a compromise: the device memory is limited, so there needs to be a strategy to discard old messages. A simple approach is to use a ring buffer that stores the latest messages and will discard the oldest message once its size limit is reached.

On a side note

The same is true for devices that control a system. They should have built-in decision rules and must not depend on an answer from a cloud backend to provide the action to execute based on the current condition.

4. Firmware Upgrades (FOTA)¶

Arguably a firmware upgrade over the air (FOTA) can be seen as configuration, however the size of a typical firmware image (500KB) is 2-3 magnitudes larger than a control message. Therefore it can be beneficial to treat it differently. Typically an upgrade is initiated by a configuration change, once acknowledged by the device will initiate the firmware download. The download itself is done out of band not using MQTT but HTTP(s) to reduce overhead.

Firmware upgrades are so large compared to other messages that the device may suspend all other operation until the firmware upgrade has been applied to conserve resources.

Summary¶

Bifravst aims to provide robust reference implementations for these four kinds of device data. While the concrete implementation will differ per cloud provider, the general building blocks (state, configuration, batched past state, firmware upgrades) will be the same.

Cloud |

State |

Configuration |

Past data |

FOTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

AWS |

|

|

MQTT |

Jobs + HTTPS |

GCP |

MQTT |

|||

Azure |

|

|

MQTT |